QuantumSpace – Towards a new phenomenology of the digitized artwork

Ŏpĕra Magazine

Written by Valeria Bevilacqua and Lara Gaeta

Getting to know QuantumSpace [1] up close, and spending time in conversation with its three founders, gave us the opportunity to step outside our usual perspective and look at the contemporary art system from a different angle. As curators used to working through research, writing, exhibition-making, and direct collaboration with artists, we found ourselves engaging with a set of tools and languages that didn’t belong to our field, yet resonated strongly with the kinds of questions we regularly face in our practice. It was precisely in this exchange — between contemporary art and emerging technology — that new frameworks began to emerge, helping us reflect more clearly on the limits, potential, and responsibilities of the art world as we know it.

Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and data science are not just technical tools in this context — they’re part of a broader critical framework that challenges how the art system operates, and how value is generated, tracked, and legitimized. It’s in these hybrid, often overlooked spaces that QuantumSpace has established itself, developing a model that cuts across disciplines and rethinks technology as a structural support for the artwork. The results are concrete: cryptographic certification, data-driven authorship attribution, and transparent digital archives designed not just to store work, but to ensure its traceability, preservation, and long-term valuation.

Setting the Stage

Our research in contemporary art, aesthetics, and philosophy — closely tied to curatorial practice and to ongoing work with emerging artists finds a surprising but coherent parallel in the tools developed by QuantumSpace. Their approach brings together technological innovation with methods drawn from the psychology of art and neuroaesthetics, opening up new ways to access, document, and interpret artworks. These tools address a broad network: artists, gallerists, collectors, dealers, museum professionals, researchers, and artists’ estates. For artists and galleries, this means being able to catalogue and certify their work using objective, standardized criteria. For collectors, it offers a way to trace a work’s trajectory over time — not only as an asset, but as a vehicle for identity and legacy. For institutions, it enables the construction of shared knowledge around both established and lesser-known figures. And for the public, it opens up immersive experiences — through AR, VR, and beyond — that reactivate the material, gestural, and cognitive layers embedded in the artwork.

What’s at stake here isn’t only how artworks are archived, authenticated, or accessed — but how they’re understood: as cultural objects, as relational tools, as patrimonial assets. Looking at art through this kind of hybrid, interdisciplinary lens invites us to reassess the critical tools we rely on and rethink how artistic value is framed. It also brings into focus a broader question of responsibility: who ensures the preservation of cultural meaning, and how?

If we consider artworks part of a shared cultural legacy—as we must—then their long-term care and accessibility should be seen as a collective responsibility. Institutions can’t simply preserve objects; they need to preserve meaning. And that calls for infrastructures that are transparent, inclusive, and built to endure.

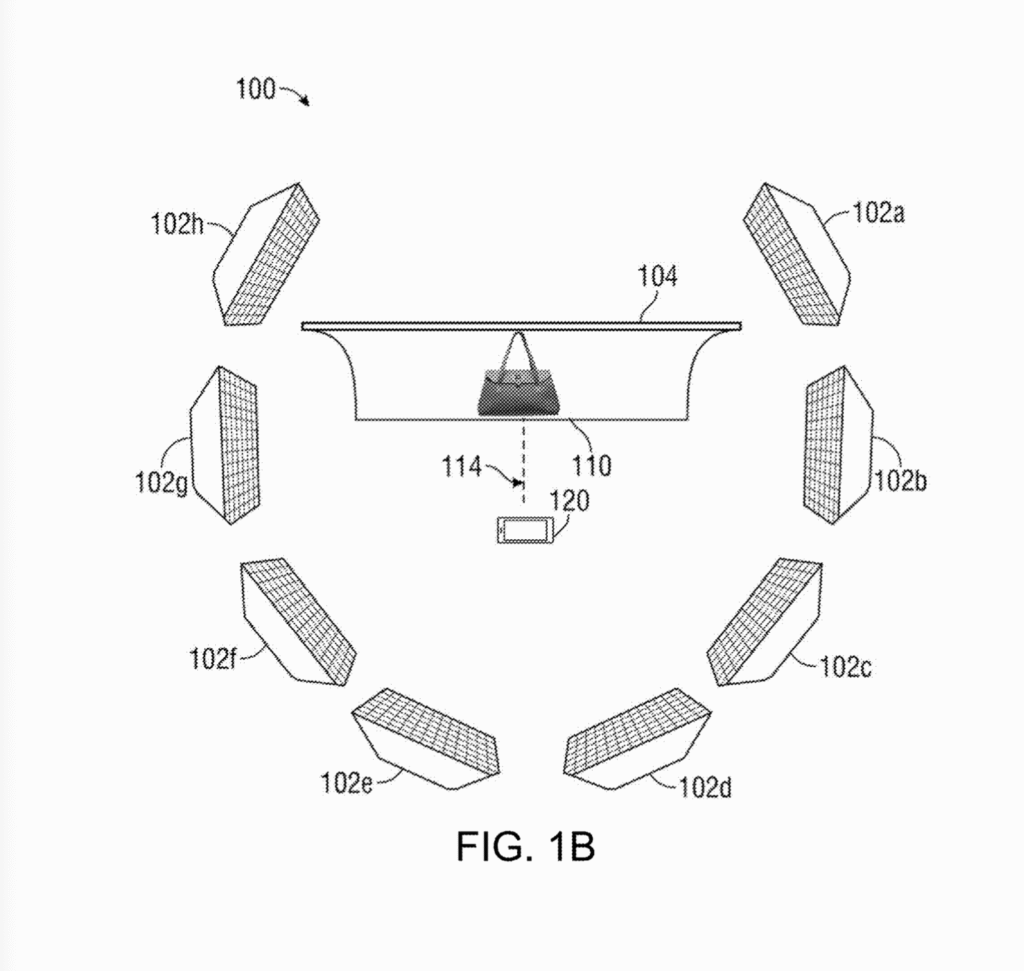

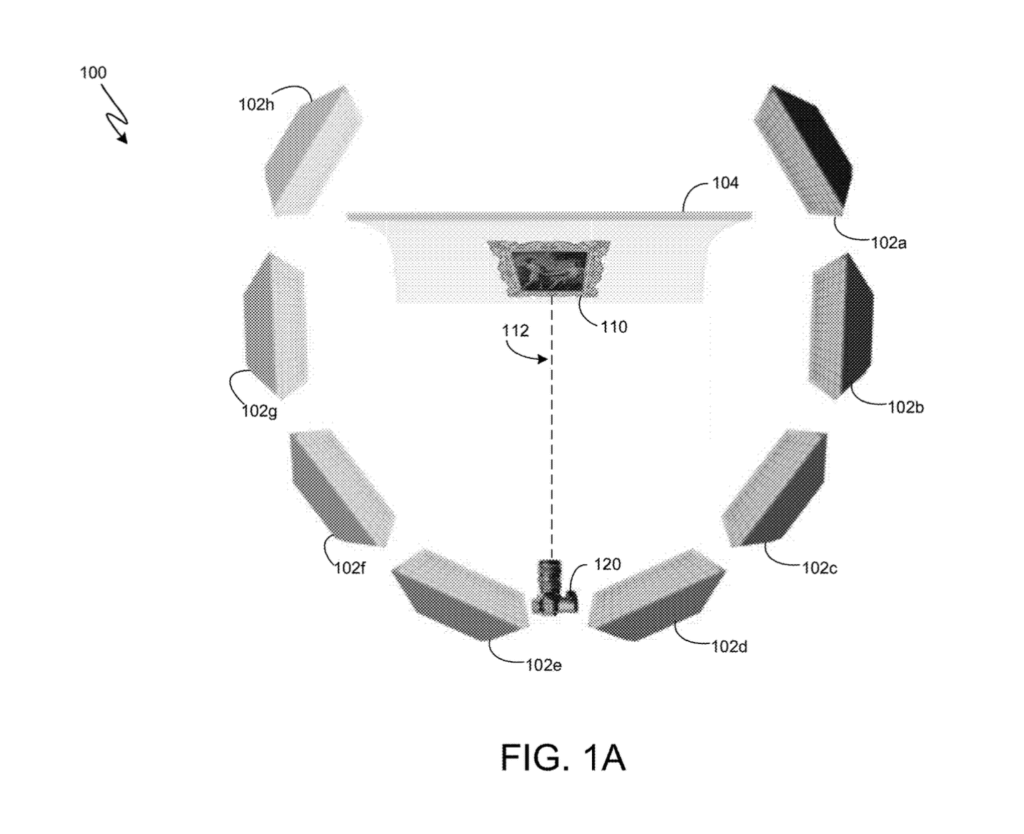

Like a “crazy quilt”: a team that navigates the complexity of the present

QuantumSpace stands today as one of the most advanced frontiers in the field of artwork digitalization and authentication on a global scale. Founded in Italy in 2019 under the name Spacefarm by Marco D’Aiuto and Alberto Finadri, the project began as a blockchain-based platform for intellectual property certification. A turning point came in 2022 with the arrival of Francesco Rocchi — a psychologist of art with a background in neuroaesthetics — who helped solidify the project’s identity and expand its interdisciplinary direction. Since then, the company has undergone steady evolution, refining its services in response to shifting market demands and the changing needs of the art world. The transition from Spacefarm to QuantumSpace, along with a full rebranding, took place in 2024 — a pivotal year in which the company specialized in the development of a patented technology for the certification and authentication of artworks. That same April, QuantumSpace was granted a U.S. patent [2] for an advanced system capable of extracting and digitizing visual data: a tool designed to automatically recognize, catalogue, and validate complex visual content by integrating machine learning, computer vision, and certified authentication protocols.

Today, the company operates in both Europe and the U.S., with a growing presence in New York, where two of the founders — Alberto and Francesco — relocated in 2024. Immersing themselves in the highly structured and fast-paced U.S. art scene allowed QuantumSpace to broaden its perspective and develop a more flexible, multi-layered approach to the industry.

The three founders bring complementary skill sets to the table, embodying what has been described in innovation circles as a “crazy quilt ” model [3]: an irregular, patchwork structure made up of distinct yet converging experiences — an approach that’s agile, responsive, and capable of adapting to complexity. Marco D’Aiuto, Chief Marketing Officer, focuses on the relationship between content and audience, acting as a bridge between technology and communication. Francesco Rocchi, Chief Operating Officer, leads on the technical and scientific side; his training in art psychology and neuroaesthetics shapes the analytical rigor of the systems developed. Alberto Finadri, Chief Executive Officer, provides strategic and financial direction, with a clear understanding of market dynamics and business operations.

QuantumSpace isn’t looking to replace traditional players in the art world. Instead, its aim is to collaborate — offering tools that integrate with and strengthen existing expertise. The goal is shared: to certify, preserve, and enhance the value of artworks and cultural heritage over time. «Making art eternal» [4], while keeping it accessible to a growing audience, is the mission driving QuantumSpace forward—through cutting-edge technologies and economically sustainable solutions.

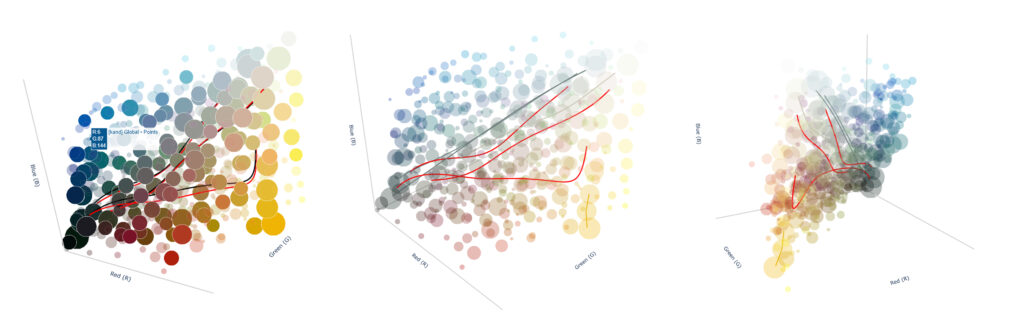

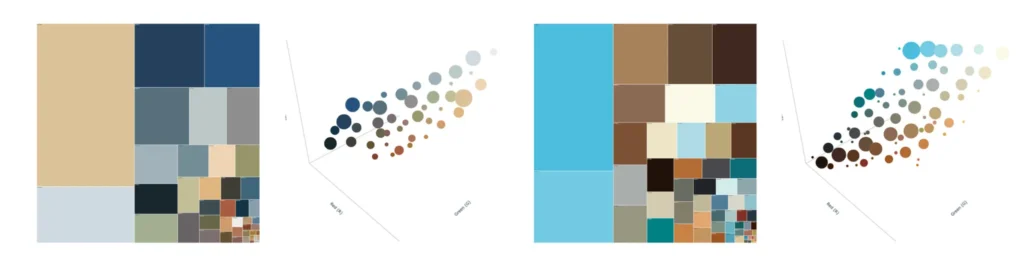

(left) Edward Hopper – Cape Cod Evening – Color Palette and Scatter Plot (right) Joaquin Sorolla – The Return from Fishing – Color Palette and Scatter Plot

The artwork in the digital sphere: the blockchain turn

At QuantumSpace, blockchain isn’t a trend — it’s part of the core architecture. From the start, it’s been used not for speculation, but as a structural tool for ensuring traceability, authorship, and long-term preservation. In the words of its founders, it was «a real game changer» [5] — for the entire art ecosystem, and for the company’s own development. The company’s entire system is built on this foundation, offering a range of services that include ultra-high-resolution digitization, analytical reports, and digital certificates of authenticity. Every record is encrypted, timestamped and immutable, guaranteeing transparency and historical continuity. Unlike conventional digital systems, which overwrite previous entries with each update, blockchain preserves every event in the life of an artwork. Sales, loans, restorations, changes of ownership: each step is registered as a new block, forming a permanent, verifiable chain.

Even in its early years, when it was still operating as Spacefarm, QuantumSpace took a clear position: distancing itself from the speculative NFT boom and instead focusing on certification — using blockchain to support provenance and cultural value [6], not hype. At a time when the line between digital art and crypto art was still blurry — even within the art world — QuantumSpace made an important distinction. Digital art [7], they argued, is a mature, historically grounded practice. Crypto art, by contrast, emerged from a different context: one driven by new modes of exchange and decentralized systems of validation [8]. The phenomenon began around 2014, but reached global visibility in 2021, when Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days sold at Christie’s for over $69 million [9] — an unprecedented moment that reframed what digital art could mean in the marketplace.Today, QuantumSpace’s work centers around two core services: the digital certification report and the Author’s Digital Archive, which is currently under active development.

(left) Mary Cassat – Little Girl in a Blue Armchair – Zenital

(middle) Paul Cezanne – Still Life with Apples and Peaches – Zenital

(right) Winslow Homer – Breezing Up (A Fair Wind) – Zenital

Beyond the surface: the digital report and authorial patterns

The digital certification report developed by QuantumSpace enables an in-depth examination of every material and structural aspect of a work of art. In the case of paintings, it reveals not only the artist’s color techniques, compositional decisions, and brushstroke directions, but also unconscious and recurring gestures — distinctive traits of a single artist’s identity that are impossible to misread or replicate. Each report is based on the collection and analysis of an average of three million data points, processed through a fully non-invasive methodology. This system offers a compelling alternative to more traditional tools of dating and attribution — such as radiocarbon analysis — which require the extraction of a physical sample from the artwork. With an authorship attribution accuracy of 99.8%, QuantumSpace’s system — powered by AI trained to recognize stylistic, gestural, and material patterns — enables the precise identification of an artist’s hand, far beyond the reliability of traditional methods [10]. As the team explains, «we moved from a blockchain-based approach to a more complex form of authentication, made possible by our patent and AI systems. Today we can enter the work, identify the author’s key traits, and prevent cases of forgery or fraud» [11]. One of the most widely debated cases in recent years remains that of the Salvator Mundi, attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and sold at Christie’s in 2017 for over $450 million [12]. This record-breaking sale sparked an international debate on the painting’s authenticity [13] – highlighting the urgent need for verifiable, objective tools such as those developed by QuantumSpace.

A particularly significant example, this time in the field of sculpture, is the digitalization of the Apollo of Mantua, a Roman marble statue from the 2nd century CE housed at the Palazzo Ducale [14]. The sculpture is a marble copy of a likely bronze Greek original, depicting the god Apollo in a classic contrapposto pose. Its iconography represents a variation on the Apollo Citharoedus type — the god of music playing the lyre. Today, the work is in a fragile state of conservation: the right arm is missing, several surfaces are chipped, and other elements—such as the laurel crown, the serpent’s head, and the support trunk — have been reconstructed in plaster. In 2024, QuantumSpace undertook a comprehensive digitalization of the sculpture, combining ultra-high-resolution imaging, 3D reconstruction, and algorithmic analysis. This fully non-invasive process enabled a dual outcome: it preserved a detailed digital record of the sculpture’s current condition, while also generating a philological reconstruction — such as the likely positioning of the missing arm — with unprecedented precision. The technology made it possible to detect fine details invisible to the naked eye, including cracks, abrasions, and poorly executed restorations, providing valuable analytical tools for both restorers and scholars. An interactive 3D model now offers an immersive experience of the work, making it accessible not only to experts, but also to a wider audience interested in engaging with heritage through innovative formats. This intervention demonstrates how, even in the case of archaeological works with complex histories, a computational and algorithmic approach can offer new critical, conservation, and museographic perspectives — restoring the work’s integrity while enhancing its accessibility and readability over time.

Unknown Artist – Mantua’s Apollo – 3D Reconstruction

High-definition digitalization thus becomes the starting point for a deeper visual and structural analysis. The process combines multispectral imaging, macro photography, and raking light to produce a high-resolution 3D map that captures even the most subtle surface textures. Supporting this analysis is a 3D viewer, which allows users to explore the artwork digitally and interactively. The evaluation is further enriched by relational data modeling that takes into account interactions and co-variations across multiple works by the same author. This approach helps approximate a true “aesthetic signature” — a coherent constellation of color, compositional, and formal choices, as well as recurring behavioral structures, all attributable to a single artist [15]. It is precisely within this tension — between computational objectivity and artistic sensibility — that the digital report acquires its critical value, offering a new way to interpret, transmit, and safeguard works of art. A particularly refined demonstration of this method is the 2025 analysis of Leonardo da Vinci’s Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci , painted circa 1474–1478 and now held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. The analysis provides a multilayered reading of the work, revealing with remarkable clarity Leonardo’s stylistic decisions, tonal transitions, surface textures, and visible signs of aging — like craquelure patterns that indicate vulnerable areas in the painting’s material structure. These data points form the basis for predictive conservation, focused not only on diagnosis but on anticipating future deterioration. The volumetric color extraction produces what QuantumSpace calls a “chromatic sculpture” — a 3D rendering of Leonardo’s palette that enriches the structural and aesthetic reading of the painting. In this case, technology doesn’t replace the work of the art historian — it reinforces it, extending the scope of what’s visible. Interactive maps, histograms, and sectional visualizations reveal the technical complexity and refined execution of this iconic piece. Ginevra de’ Benci was not just any sitter: she was one of the most cultured women of fifteenth-century Florence, as described by Lorenzo de’ Medici. Her unflinching gaze and luminous, alabaster complexion are reactivated in the digital rendering with a renewed expressive presence. The report and its data visualizations allow not only for a critical rereading of the work, but also for a deeper entry into the “psychological dimension” [16] of the portrait — restoring Ginevra’s dignity, and revealing a timeless beauty.

Leonardo da Vinci – Ritratto di Ginevra de Benci – Artwork Analysis

The patrimonial shift: the artwork between augmented memory and digital preservation

The digital archive is a platform designed to offer artists, collectors, galleries, institutions, and auction houses an advanced tool for managing, preserving, and enhancing the value of artworks. Each work is digitized using QuantumSpace’s proprietary technology, ensuring authenticity, traceability, and long-term monitoring of its cultural and financial value. The result is a customizable, elegant, and functional website — an interactive digital archive where each piece is presented through ultra-high-resolution images, a blockchain-based certificate of authenticity, and descriptive records detailing its history, technique, and creative process. Unlike traditional systems — still often reliant on paper-based or notarial procedures—certification through QuantumSpace takes place entirely in a secure, legally valid, and remotely accessible digital environment. This makes the archive adaptable to a wide range of users: for artists, it may serve as a platform for documenting and enhancing their body of work; for collectors, it may function as an updatable digital portfolio; for museums and foundations, it can become a powerful cataloguing tool — particularly valuable in giving visibility to works currently held in storage. Globally, in fact, it is estimated that up to 90% of museum collections are kept in non-exhibition storage areas, and therefore remain inaccessible to the public. This figure, widely documented in international museological literature, raises important questions about the mission of cultural institutions and the true accessibility of heritage assets [17]. Even for auction houses, adopting a blockchain-based archive represents a strategic advantage — streamlining authentication processes, reducing time and cost, and providing a robust documentary foundation to support provenance and attribution.

Each item in the archive can be enriched with multimedia content — studio footage, interviews, behind-the-scenes material — that deepens the narrative and enhances communication around the work. In this context, digitalization does not imply a loss of material presence; rather, it acts as a form of “displacement” [18]: a relocation of the work into a structured, accessible, and monitorable digital environment. Here, the aura of the original doesn’t disappear — it is reframed, preserved, and opened up to new modes of engagement and understanding. Within QuantumSpace’s orbit — where AI, machine learning, data science, blockchain, and algorithmic systems converge — the artwork takes on new configurations. Its historical placement becomes just one among many possible coordinates. The work emerges as a quantum object: one that stretches across time and space, blending past, present, and future; material presence and digital potential. A perhaps unintended — but not insignificant — side effect of Quantumspace’s model is its ability to expose the stress points of the art system. Though not aiming to replace its traditional players, it sometimes brings their fragilities to the surface. And that, arguably, is no bad thing. Because friction creates space: space for reflection, for critique, for transformation. If art today also engages with datasets, patents, and neural simulations, that doesn’t mean we must abandon its intuitive, relational, or emotional dimensions. On the contrary – these technologies demand a more sensitive gaze: one that can inhabit the threshold between algorithm and aura, between archive and imagination.

What will the artworks of the future look like? What will creativity mean in a context where artificial intelligence becomes co-author of the aesthetic process? Does technology shape human thought, or is it human thought that reconfigures technology?

Perhaps what we need now are not definitive answers — but better questions. And a space in which to keep asking them.

References

[2] Francesco Rocchi; Alberto Finadri, System and method for automatic authentication of artworks , U.S. Patent No. 11,948,386, registered with the USPTO (United States Patent and Trademark Office), 16 April 2024.

[3] Saras D. Sarasvathy, Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008. The principle of the «crazy quilt » refers to a non-linear entrepreneurial approach in which the involved partners — often with very different skill sets — contribute to building a shared project by progressively adapting to context and emerging opportunities.

[4] Interview with the founders, 11 April 2025.

[5] Interview with the founders, 26 March 2025.

[6] Amy Whitaker, Art and Blockchain: A Primer, History, and Taxonomy of Blockchain Use Cases in the Arts , «Artivate», 8 (2019), no. 2, pp. 21–46.

[7] The expression «digital art» began to circulate in the early 1980s, but its roots go back to the 1960s, with the first artistic experiments carried out by pioneers such as John Whitney, Frieder Nake and Harold Cohen. See Christiane Paul, Digital Art , Londra: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

[8] Massimo Franceschet [et al.], Crypto Art: A Decentralized View , «Leonardo», 54 (2021), n. 4, pp. 402–405.

[9] Filomena Dardano, Crypto Art: come la tecnologia blockchain sta rivoluzionando il settore artistico , «24Ore Business School», March 3, 2023.

[10] The average accuracy of expert attribution, according to various studies, ranges between 60% and 80%, with margins of error increasing in the absence of reliable documentation or in cases involving school or workshop productions. The debate surrounding the reliability of expert judgment remains open and cuts across both aesthetics and computational sciences. See J.O. Young, Art Authentication and the Epistemology of Attribution , «British Journal of Aesthetics», 2005; D. Leonard; I. Daubechies, A Machine Learning Approach to Assessing Art Attribution , in «PNAS», 2019; D. Stork, Computer Vision and Computer Graphics Analysis of Paintings and Drawings , «IJDAH», 2015.

[11] Interview with the founders, March 26, 2025.

[12] Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi makes auction history , «Christie’s», November 15, 2017.

[13] See Brigit Katz, Why Critics Are Skeptical About the Record-Smashing $450 Million da Vinci , «Smithsonian Magazine», November 16, 2017; Matthew Landrus, Kabir Jhala, La vita tormentata del “Salvator Mundi” , in «Il Giornale dell’Arte», December 8, 2022.

[14] See General Catalogue of Cultural Heritage (digital format), Apollo (so-called Apollo of Mantua), sculpture 150–174.

[15] Francesco Rocchi, Automating Aesthetic Intelligence: Exploring Advanced Data Extraction and Computational Modeling Applications for Art Analysis and Creative Market Security , internal white paper, Quantumspace, 2023.

[16] Frank Zöllner, Leonardo da Vinci’s Portraits: Ginevra de’ Benci, Cecilia Gallerani, La Belle Ferronière, and Mona Lisa , Leipzig: Institut für Kunstgeschichte, Universität Leipzig, 2003, p. 162

[17] ICCROM, RE-ORG – Collection Storage Reorganization , Rome: International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property, 2011; Lara Corona, Digitization for the Visibility of Collections , «Collection and Curation», 42 (2023), no. 3, pp. 73–80; ICOM – International Council of Museums, Museum Storage around the World , Paris: ICOM, 2024

[18] See in particular Fiona Cameron, Beyond the Cult of the Replicant: Museums and Historical Digital Objects , in Fiona Cameron & Sarah Kenderdine (eds.), Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage , MIT Press, Cambridge MA, 2007, pp. 49-76. Cameron analyses the concept of digital “displacement” as a semantic and functional relocation of the museum object within computational systems and interactive archives, redefining its conditions of access, interpretation, and preservation.